MESSY PRAYER

True intercession is like a couple of musicians playing off one another until a new sound is made and a new song can be sung

A natural response to rapid change is to impose some kind of order on it. No wonder then, in this giddying millennial era, that the measure of success is the degree of control we can exhibit. We test, mark and audit one another relentlessly, aided by big data and the ability to process information quickly. Perhaps this is one cause of so much more controlling behaviour, where we impose our will reflexively on our environment, without seeing how much we limit the freedom of others to act as they would like to.

Is there a chance that controlling behaviour is manifesting itself more in our prayers? At face value, scripture seems to legitimate it. Abraham barters with God over the fate of Sodom; Jacob wrestles with God and will not let go until he is blessed; Gideon gives God a mat and tells him what to do with it. Yet each man knew something about the character of God: the mercy that could save a city; the faithfulness that would surround a disloyal brother; the gentleness that would give assurance to a fearful man.

Penetrating intercessors know the character and promises of God and are unafraid to remind him of them. Praying Daniel, surveying the catastrophe of exile, picked out the promise of God from Jeremiah’s mouth that a generation’s pain was now complete. Prayer may be a mystery, but there is a certain rationality about it. We can name people, places, circumstances, put them in order and call to mind the kind of God we believe in and how he might respond to us. But what happens when we get into the habit of telling God what to do?

The more rushed we are, the more likely it is we try to exercise control over God. We expect him to join the dots, so there is unbroken clarity and purpose to our lives. Fragmented, hurried prayer is like the harassed boss barking instructions into a phone. It is the product of an excessive form of control, where we tell God what to do to make situations better. We assume that rushed prayer is fragmented, but it may congeal into a pathological orderliness.

When the apostle Peter was imprisoned and on the verge of execution early in his ministry, the Church prayed for him, not for his release. Their expectant hope was bathed in worship and lacked the kind of direction we would have imposed. And they took time to pray too, exposing themselves to the temptation to tell God what to do.

We may know the character of God, but there is a mysterious sovereignty at work which we have to respect, however hard that may feel. When we bemoan unanswered prayer we rarely stop to think how we framed our request in the first place. Rather than asking for God’s genius and spontaneity to be freely expressed, we may have put God in the kind of straightjacket associated with a legal contract, where terms and conditions are imposed, setting us up for disappointment.

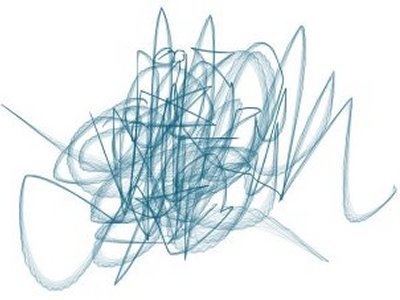

Truly messy prayer allows God to be God, affords scope, respects ingenuity and asks for the faith to see what he does with it. Every instinct in us is to collect intercessions into neat piles which can be easily referenced by the one who receives them; the bureaucratisation of prayer. Messy prayer is a more dynamic, creative idea, like a couple of musicians playing off one another until a new sound is made and a new song can be sung.

POPULAR ARTICLES

Obama's Covert Wars

The use of drones is going to change warfare out of all recognition in the next decades.

Through A Glass Starkly

Images of traumatic incidents caught on mobile phone can be put to remarkable effect.

What Are British Values?

Is there a British identity and if so, what has shaped the values and institutions that form it?